|

1 октября отправила на проверку первое задание, до сих пор не проверено, по этой причине не могу пройти последующие тесты. |

Error

GROUPING ERRORS.

This involves looking for patterns of errors in your students’ work. For example, all errors with the past tense can be underlined and marked with a 1 in the margin. Spelling errors involving homophones (their/there) could be marked with a 2 and so on, up to no more than 4 points. At the end of the students’ work you can discuss the error and choose an exercise to correct it.

SELF-CHECK 3:5 3

Sometimes you have to look carefully to identify a pattern of error.

In the following passage, a 14 year old in an international school is writing about a project to do with developing a robot. But there is something very specific wrong with this piece of writing. Can you spot it?

We had a lot of problems to overcome like the movement of the robot, it was too slow and we increased the speed. The things he does well - he is good at socializing and makes a decent conversation.

The robot still has no strength to pick up grocery bags, we need to make him a bit stronger. We need to add a dictionary and encyclopedia to the robot, people can ask him questions and he tells them the answer. We also found out the robot cannot keep messages from the phone, the memory has been expanded.

COMMENT 3:5 3

This student at first seems to be a good writer as there are no spelling or word formation problems. But he cannot express cause and effect with because or so. There are no connectives between clauses. Look again; it is a little tricky to spot, as at first glance the writing makes sense.

The student was given remedial exercises to do in this area.

SELF-CHECK 3:5 4

CAN YOU PUT a number 1 in the margin of this piece of work wherever there is this problem with cause and effect and write a comment to bring the student’s attention to the problem. Tell them what they are doing wrong.

Your comment: __________________________________________________________

SELECTIVE MARKING

This means focusing on one thing to mark in a piece of work. This needs to be announced before a piece of work is handed in, through discussion with the students so they are clear about what will happen.

Tell the students that in their next piece of work you will be looking specifically at past tense forms and how well they can use them

OR

They have to include the key vocabulary you have learnt in a paragraph and get points for doing so

OR

You could have a focus on politeness and use of formal language with credit given for having the right tone.

Teachers often set up tasks like this and then when they get the work, cover it in red pen for all sorts of errors that have nothing to do with the task - this is not a good way to help the students.

When you mark the work that has a target, mark in a coloured pen and a pencil. Mark all the good instances of use in the piece and the errors with key forms in the coloured pen, using a number grouping as above if you wish.

Mark all other mistakes only lightly in pencil to show that these are not the ones that were being concentrated on. Make a comment about how well the target was reached. (Some teachers prefer not to mark other errors even lightly in pencil - you may have to be guided by your class on this issue. For example many students will take issue with a teacher who does not point out their mistakes, even if these mistakes are not relevant to the lesson).

In this situation and indeed on every piece of work ALWAYS tick or comment on good work. You are there to see what the student has done well as well as what they have made mistakes with.

SELF-CHECK 3:5 5

Here is another section from the ski trip story: This time mark the piece three times using three different colours.

1st time: Mark only for spelling and comment on it.

2nd time: Mark only for tense use. Are the tense forms well controlled?

3rd time: Mark positively for elements of a good story.

It looked dangerous with small ice ships roling losely in the wind and the frezing ice glitering in the sun. People shouted:

"What are you doing up there?"

"Come on!"

Feeling confident and brave but still with a look of fear on my face, I cleared my mind of everything, and pushed off with my sticks.

At first I feeled as if I was OK but then I started to go out of control. My sticks flied from my hands. I could hear my skis scrapping on the ice. Then the scrapping stoped and I feeled myself hurled into the air. For about what seemed like an age I seed a blur of little woden huts and other people skiing as I flied through the air…

COMMENT

You should have spotted that this is a good descriptive piece of writing.

There are patterns in the spelling errors and in the tense errors and they are not random so you should be able to praise this student for a good piece of writing and give very clear advice as to what to practise for next time.

RESPONDING TO CONTENT

Whenever you are doing a realistic writing task that involves the student following a plan and producing a piece of writing into which they have put imagination or facts of interest then you MUST respond as a person as well as a teacher. These comments do not have to be long and complicated but are good for student morale.

The ski story ends like this:

At 3 o’clock that afternoon Mr Leboeuf taked me to the Verbier medic centre. I don’t remember much about ospital but it was clean and tiddy. The doctor sayed I have sprained the ligaments in my knee and that I have to have a brace on my leg and CRUTCHES!

Appropriate comments on content would be:

How long did you have the brace on your leg? And the crutches?

I think you were very brave, but you were going too fast, weren’t you?

A very well written and interesting story.

Now consider the following extract:

Assessing student performance can come from the teacher or from the students themselves.

Teachers assessing students

Assessment of performance can be explicit when we say That was really good, or implicit when, during a language drill, for example, we pass on to the next student without making any comment or correction (there is always the danger, however, that the student may misconstrue our silence as something else).

Students are likely to receive teacher assessment in terms of praise or blame. Indeed, one of our roles is to encourage students by praising them for work that is well done. Praise is a vital component in a student's motivation and progress. George Petty sees it as an element of a two-part response to student work. He calls these two parts 'medals' and 'missions'. The medal is what we give students for doing something well, and the mission is the direction we give them to improve. We should 'try to give every student some reinforcement every lesson' (2004: 72) and avoid only rewarding conspicuous success. If, he suggests, we measure every student against what they are capable of doing - and not against the group as a whole - then we are in a position to give medals for small things, including participation in a task or evidence of thought or hard work, rather than reserving praise for big achievements only.

While it is true that students respond well to praise, over-complimenting them on their work - particularly where their own self-evaluation tells them they have not done well - may prove counter-productive. In the first place, over-praise may create 'praise junkies' (Kohn 2001), that is students who are so addicted to praise that they become attention seekers and their need for praise blinds them to what progress they are actually making. Secondly, students learn to discriminate between praise that is properly earned and medals (in Petty's formulation) that are given out carelessly. This is borne out in research by Caffyn (1984, discussed in Williams and Burden 1997: 134-136) in which secondary students demonstrated their need to understand the reasons for the teacher's approval or disapproval. Williams and Burden also point to the ineffectiveness of blame in the learning process.

What this suggests is that assessment has to be handled with subtlety. Indiscriminate praise or blame will have little positive effect - indeed it will be negatively received - but a combination of appropriate praise together with helpful suggestions about how to improve in the future will have a much greater chance of contributing to student improvement.

It is sometimes tempting to concentrate all our feedback on the language which students use, such as incorrect verb tenses, pronunciation or spelling, for example, and to ignore the content of what they are saying or writing. Yet this is a mistake, especially when we involve them in language production activities. Whenever we ask students to give opinions or write creatively, whenever we set up a role-play or involve students in putting together a school newspaper or in the writing of a report, it is important to give feedback on what the students say rather than just on how they say it. Apart from tests and exams, there are a number of ways in which we can assess our students' work:

- Comments: commenting on student performance happens at various stages both in and outside the class. Thus we may say Good, or nod approvingly, and these comments (or actions) are a clear sign of a positive assessment. When we wish to give a negative assessment, we might do so by indicating that something has gone wrong (see below), or by saying things such as That's not quite right. But even here we should acknowledge the students' efforts first (the medal) before showing that something is wrong - and then suggesting future action (the mission). When responding to students' written work, the same praise-recommendation procedure is also appropriate, though here a lot will depend on what stage the students' writing is at. In other words, our responses to finished pieces of written work will be different from those we give to help students as they work with written drafts.

- Marks and grades: when students are graded on their work, they are always keen to know what grades they have achieved. Awarding a mark of 9 out of 10 for a piece of writing or giving a B+ assessment for a speaking activity are clear indicators that students have done well. When students get good grades, their motivation is often positively affected - provided that the level of challenge for the task was appropriate. Bad grades can be extremely disheartening. Nor is grading always easy and clear cut. If we want to give grades, therefore, we need to decide on what basis we are going to do this and we need to be able to describe this to the students. When we grade a homework exercise (or a test item) which depends on multiple choice, sentence fill-ins or other controlled exercise types, it will be relatively easy for students to understand how and why they achieved the marks or grades which we have given them. But it is more difficult with more creative activities where we ask students to produce spoken or written language to perform a task. In such cases our awarding of grades will necessarily be somewhat more subjective. It is possible that despite this our students will have enough confidence in us to accept our judgement, especially where it coincides with their own assessment of their work. But where this is not the case - or where they compare their mark or grade with other students and do not agree with what they find - it will be helpful if we can demonstrate clear criteria for the grading we have given, either offering some kind of marking scale, or some other written or spoken explanation of the basis on which we have made our judgement. Awarding letter grades is potentially awkward if people misunderstand what the letters mean. In some cultures success is only achieved if the grade is X, whereas for people in other education systems a 'B' indicates a good result. If, therefore, we wish to rely on grades like this, our students need to be absolutely clear about what such grades mean - especially if we wish to add plus and minus signs to them (e.g. C++ or A-). Though grades are popular with students and teachers, some practitioners prefer not to award them because they find the difference between an A and a B difficult to quantify, or because they can't see the dividing line between a 'pass' and a 'distinction' clearly. Such teachers prefer to rely on comments to give feedback. They can give clear responses to the students in this way without running the risk of grading them erroneously or demotivating them unnecessarily. If we do use marks and grades, however, we can give them after an oral activity, for a piece of homework or at the end of a period of time (a week or a semester).

- Reports: at the end of a term or year some teachers write reports on their students' performance, either for the student, the school or the parents of that student. Such reports should give a clear indication of how well the student has done in the recent past and a reasonable assessment of their future prospects. It is important when writing reports to achieve a judicious balance between positive and negative feedback, where this is possible. As with all feedback, students have a right (and a desire) to know not only what their weaknesses may be, but also what strengths they have been able to demonstrate. Reports of this kind may lead to future improvement and progress. The chances for this are greatly increased if they are taken together with the students' own assessment of their performance.

Students assessing themselves

Although, as teachers, we are ideally placed to provide accurate assessments of student performance, students can also be extremely effective at monitoring and judging their own language production. They frequently have a very clear idea of how well they are doing or have done, and if we help them to develop this awareness, we may greatly enhance learning.

Student self-assessment is bound up with the whole matter of learner autonomy since if we can encourage them to reflect upon their own learning through learner training or when on their own away from any classroom, we are equipping them with a powerful tool for future development.

Involving students in assessment of themselves and their peers occurs when we ask a class Do you think that's right? after writing something we heard someone say up on the board, or asking the class the same question when one of their number gives a response. We can also ask them at the end of an activity how well they think they have got on - or tell them to add a written comment to a piece of written work they have completed, giving their own assessment of that work. We might ask them to give themselves marks or a grade and then see how this tallies with our own.

Self-assessment can be made more formal in a number of ways. For example, at the end of a coursebook unit we might ask students to check what they can now do, e.g. 'Now I know how to get my meaning across in conversation/use the past passive/interrupt politely in conversation', etc.

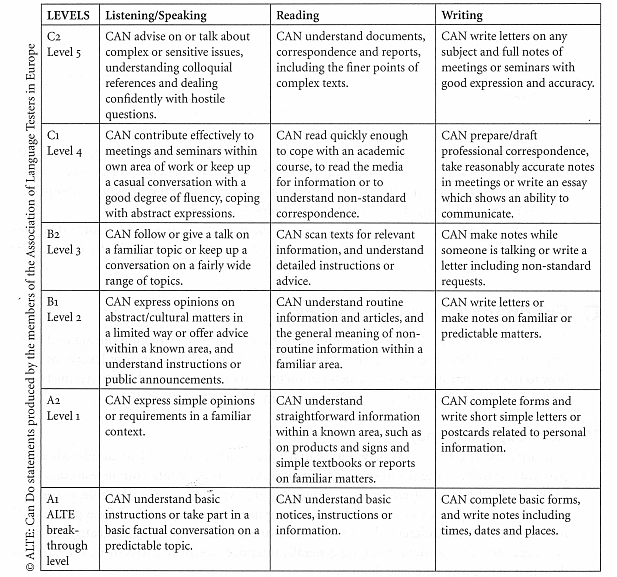

This kind of self evaluation is at the heart of the 'can do' statements from ALTE (Association of Language Testers in Europe) and the Common European Framework (CEF). Students - in many different languages - can measure themselves by saying what they can do in various skill areas. The ALTE statements for general overall ability (giving six levels from A1-C2), give students clear statements of ability against which to measure themselves:

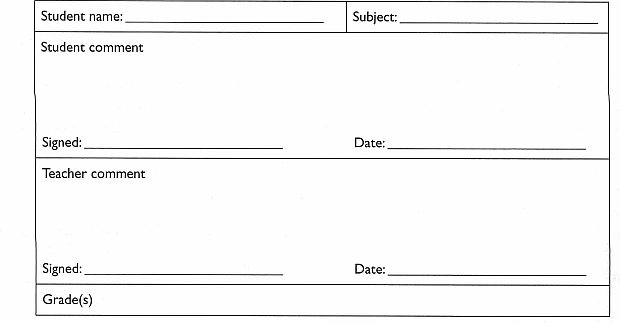

A final way of formalising an assessment dialogue between teacher and student is through a record of achievement (ROA). Here, students are asked to write their own assessment of their successes and difficulties and say how they think they can proceed. The teacher then adds their own assessment of the students' progress (including grades), and replies to the points the student has made. A typical ROA form can be seen in Figure 9.2.

Such ROAs, unlike the more informal journal and letter writing which students and teachers can engage in, force both parties to think carefully about strengths and weaknesses and can help them decide on future courses of action. They are especially revealing for other people, such as parents, who might be interested in a student's progress.

Where students are involved in their own assessment, there is a good chance that their understanding of the feedback which their teacher gives them will be greatly enhanced as their own awareness of the learning process increases.