| Сколько по времени занимает проверка заданий? |

Learning and teaching

Pairwork

In pairwork, students can practise language together, study a text, research language or take part in information-gap activities. They can write dialogues, predict the content of reading texts or compare notes on what they have listened to or seen.

Advantages of pairwork:

- It dramatically increases the amount of speaking time any one student gets in the class.

- It allows students to work and interact independently without the necessary guidance of the teacher, thus promoting learner independence.

- It allows teachers time to work with one or two pairs while the other students continue working.

- It recognises the old maxim that 'two heads are better than one', and in promoting cooperation, helps the classroom to become a more relaxed and friendly place. If we get students to make decisions in pairs (such as deciding on the correct answers to questions about a reading text), we allow them to share responsibility, rather than having to bear the whole weight themselves.

- It is relatively quick and easy to organise.

Disadvantages of pairwork:

- Pairwork is frequently very noisy and some teachers and students dislike this. Teachers in particular worry that they will lose control of their class.

- Students in pairs can often veer away from the point of an exercise, talking about something else completely, often in their first language. The chances of misbehaviour are greater with pairwork than in a whole-class setting.

- It is not always popular with students, many of whom feel they would rather relate to the teacher as individuals than interact with another learner who may be just as linguistically weak as they are.

- The actual choice of paired partner can be problematic (see below), especially if students frequently find themselves working with someone they are not keen on.

Groupwork

We can put students in larger groups, too, since this will allow them to do a range of tasks for which pairwork is not sufficient or appropriate. Thus students can write a group story or role-play a situation which involves five people. They can prepare a presentation or discuss an issue and come to a group decision. They can watch, write or perform a video sequence; we can give individual students in a group different lines from a poem which the group has to reassemble. In general, it is possible to say that small groups of around five students provoke greater involvement and participation than larger groups. They are small enough for real interpersonal interaction, yet not so small that members are over-reliant upon each individual. Because five is an odd number it means that a majority view can usually prevail. However, there are occasions when larger groups are necessary. The activity may demand it or we may want to divide the class into teams for some game or preparation phase.

Advantages of groupwork:

- Like pairwork, it dramatically increases the number of talking opportunities for individual students.

- Unlike pairwork, because there are more than two people in the group, personal relationships are usually less problematic; there is also a greater chance of different opinions and varied contributions than in pairwork.

- It encourages broader skills of cooperation and negotiation than pairwork, and yet is more private than work in front of the whole class. Lynne Flowerdew (1998) found that it was especially appropriate in Hong Kong, where its use accorded with the Confucian principles which her Cantonese-speaking students were comfortable with. Furthermore, her students were prepared to evaluate each other's performance both positively and negatively where in a bigger group a natural tendency for self-effacement made this less likely.

- It promotes learner autonomy by allowing students to make their own decisions in the group without being told what to do by the teacher.

- Although we do not wish any individuals in groups to be completely passive, nevertheless some students can choose their level of participation more readily than in a whole-class or pairwork situation.

Disadvantages of groupwork:

- It is likely to be noisy (though not necessarily as loud as pairwork can be). Some teachers feel that they lose control, and the whole-class feeling which has been painstakingly built up may dissipate when the class is split into smaller entities.

- Not all students enjoy it since they would prefer to be the focus of the teacher's attention rather than working with their peers. Sometimes students find themselves in uncongenial groups and wish they could be somewhere else.

- Individuals may fall into group roles that become fossilised, so that some are passive whereas others may dominate.

- Groups can take longer to organise than pairs; beginning and ending groupwork activities, especially where people move around the class, can take time and be chaotic.

Ringing the changes

Deciding when to put students in groups or pairs, when to teach the whole class or when to let individuals get on with it on their own will depend upon a number of factors:

The task: if we want to give students a quick chance to think about an issue which we will be focusing on later, we may put them in buzz groups where they have a chance to discuss or buzz the topic among themselves before working with it in a whole-class grouping. However, small groups will be inappropriate for many explanations and demonstrations, where working with the class as one group will be more suitable. When students have listened to a recording to complete a task or answer questions, we may let them compare their answers in quickly-organised pairs. If we want our students to practise an oral dialogue quickly, pairwork may be the best grouping, too. If the task we wish our students to be involved in necessitates oral interaction, we will probably put students in groups, especially in a large class, so that they all have a chance to make a contribution. If we want students to write sentences which demonstrate their understanding of new vocabulary, on the other hand, we may choose to have them do it individually. Although many tasks suggest obvious student groupings, we can usually adapt them for use with other groupings. Dialogue practice can be done in pairs, but it can also be organised with two halves of the whole class. Similarly, answering questions about a listening extract can be an individual activity or we can get students to discuss the answers in pairs. We can also have a 'jigsaw listening', where different students listen to different parts of a text so that they can then reassemble the whole text in groups.

Variety in a sequence: a lot depends on how the activity fits into the lesson sequences we have been following and are likely to follow next. If much of our recent teaching has involved whole-class grouping, there may be a pressing need for pairwork or groupwork. If much of our recent work has been boisterous and active, based on interaction between various pairs and groups, we may think it sensible to allow students time to work individually to give them some breathing space. The advantage of having different student groupings is that they help to provide variety, thus sustaining motivation.

The mood: crucial to our decision about what groupings to use is the mood of our students.

Changing the grouping of a class can be a good way to change its mood when required. If students are becoming restless with a whole-class activity - and if they appear to have little to say or contribute in such a setting - we can put them in groups to give them a chance to re-engage with the lesson. If, on the other hand, groups appear to be losing their way or not working constructively, we can call the whole class back together and re-define the task, discuss problems that different groups have encountered or change the activity.

Organising pairwork and groupwork

Sometimes we may have to persuade reluctant students that pairwork and groupwork are worth doing. They are more likely to believe this if pair and group activities are seen to be a success. Ensuring that pair and group activities work well will be easier if we have a clear idea about how to resolve any problems that might occur.

Making it work

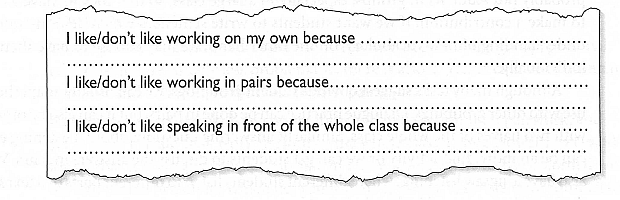

Because some students are unused to working in pairs and groups, or because they may have mixed feelings about working with a partner or about not having the teacher's attention at all times, it may be necessary to invest some time in discussion of learning routines. Just as we may want to create a joint code of conduct so we can come to an agreement about when and how to use different student groupings. One way to discuss pairwork or groupwork is to do a group activity with students and then, when it is over, ask them to write or say how they felt about it (either in English or their own language). Alternatively, we can initiate a discussion about different groupings as a prelude to the use of groupwork and pairwork. This could be done by having students complete sentences such as:

They can then compare their sentences with other students to see if everyone agrees. We can also ask them to list their favourite activities and compare these lists with their classmates. When we know how our students feel about pairwork and groupwork, we can then decide, as with all action research, what changes of method, if any, we need to make. We might decide that we need to spend more time explaining what we are doing; we might concentrate on choosing better tasks, or we might even, in extreme cases, decide to use pairwork and groupwork less often if our students object strongly to them. However, even where students show a marked initial reluctance to working in groups, we might hope, through organising a successful demonstration activity and/or discussion, to strike the right kind of bargain.

Creating pairs and groups

Once we have decided to have students working in pairs or groups, we need to consider how we are going to put them into those pairs and groups - that is, who is going to work with whom. We can base such decisions on any one of the following principles:

-

Friendship: a key consideration when putting students in pairs or groups is to make sure that we put friends with friends, rather than risking the possibility of people working with others whom they find difficult or unpleasant. Through observation, therefore, we can see which students get on with which of their classmates and make use of this observation later. The problem, of course, is that our observations may not always be accurate, and friendships can change over time. Perhaps, then, we should leave it to the students, and ask them to get into pairs or groups with whoever they want to work with. In such a situation we can be sure that members of our class will gravitate towards people they like, admire or want to be liked by. Such a procedure is likely to be just as reliable as one based on our own observation. However, letting students choose in this way can be very chaotic and may exclude less popular students altogether so that they find themselves standing on their own when the pairs

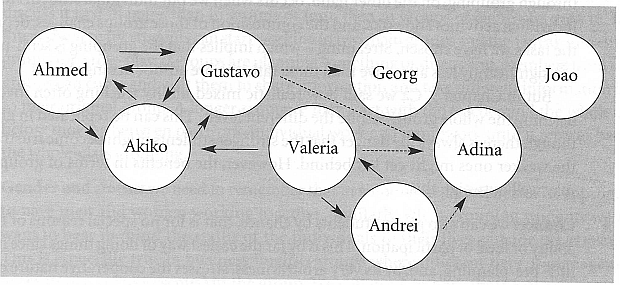

or groups are formed. A more informed way of grouping students is to use a sociogram, but in order for this to be effective (and safe), students need to know that what they write in private will never be seen by anyone except the teacher. In this procedure, students are asked to write their name on a piece of paper and then write, in order of preference, the students they like best in the class. On the other side of the piece of paper, they list the people they do not like. It is important that they know that only the teacher will look at what they have written and that they cannot be overlooked while they do this. We can now use the information they have written to make sociograms like the imaginary one in Figure 10.5:

This will then allow us to make informed choices about how we should pair and group individuals. However, not everyone agrees with the idea of grouping and pairing students in this way. In the first place, sociograms are time-consuming and fail to answer the problem of what to do with unpopular students. Secondly, some people think that instead of letting the students' likes and dislikes predominate, 'the initial likes and dislikes should be replaced by acceptance among the students' (Dornyei and Murphey 2003: 171). In other words, teachers should work to make all students accepting of each other, whoever they are paired or grouped with. Sociograms may be useful, though, when a class doesn't seem to be cohering correctly or when pairwork and groupwork don't seem to be going well. The information they give us might help us to make decisions about grouping in order to improve matters.

увеличить изображение

Рис. 10.5. Sociogram based on Roles of Teachers and Learners by T Wright (Oxford University Press) - Streaming: much discussion centres round whether students should be streamed according to their ability. One suggestion is that pairs and groups should have a mixture of weaker and stronger students. In such groups the more able students can help their less fluent or knowledgeable colleagues. The process of helping will result in the strong students themselves being able to understand more about the language; the weaker students will benefit from the help they get. An alternative view is that if we are going to get students at different levels within a class to do different tasks, we should create groups in which all the students are at the same level (a level that will be different from some of the other groups). This gives us the opportunity to go to a group of weaker students and give them the special help which they need, but which stronger students might find irksome. It also allows us to give groups of stronger students more challenging tasks to perform. However, some of the value of cooperative work - all students helping each other regardless of level - may be lost. When we discussed differentiation earlier, we saw how it was possible to help individual students with different abilities even though they were all in the same class. Streaming, therefore, seems to fit into this philosophy. However, there is the danger that students in the weaker groups might become demoralised. Furthermore, once we start grouping weaker students together, we may somehow predispose them to stay in this category rather than having the motivation to improve out of it. Successful differentiation through grouping, on the other hand, occurs when we put individual students together for individual activities and tasks, and the composition of those groups changes, depending on the tasks we have chosen. Streaming - which implies that the grouping is semi-permanent - is significantly less attractive than these rather more ad-hoc arrangements. But also we said how realistic mixed-ability teaching often involves us in teaching the whole group despite the different levels. This can be replicated in groups, too, though there is always the danger that the stronger students might become frustrated while the weaker ones might get left behind. However, the benefits in terms of group cohesion may well outweigh this.

- Chance: we can also group students by chance, that is for no special reasons of friendship, ability or level of participation. This is by far the easiest way of doing things since it demands little pre-planning, and, by its very arbitrariness, stresses the cooperative nature of working together. One way of grouping people is to have students who are sitting next or near to each other work in pairs or groups. A problem can occur, though, with students who always sit in the same place since it means that they will always be in the same pairs or groups. This could give rise to boredom over a prolonged period. Another way of organising pairwork is the 'wheels' scenario (Scrivener 2005:89). Here half of the class stand in a circle facing outwards, and the other half of the class stand in an outer circle facing inwards. The outer circle revolves in a clockwise direction and the inner circle revolves in an anti-clockwise direction. When they are told to stop, students work with the person facing them. We can organise groups by giving each student in the class (in the order they are sitting) a letter from A to E. We now ask all the As to form a group together, all the Bs to be a group, all the Cs to be a group and so on. Depending upon the size of the class, we might end up with groups of more than five, but this may not be a problem if the task is appropriate. We can also arrange random groups by asking people to get out of their chairs and stand in the order of their birthdays (with January at one end of the line and December at the other). We can then group the first five, the second five and so on. We can make groups of people wearing black or green, of people with or without glasses, or of people in different occupations (if we are in an adult class). It is interesting to note that modern computer language laboratories often have a random pairing and grouping program so that the teacher does not have to decide who should work with whom.

- The task: sometimes the task may determine who works with whom. For example, if we want students from different countries (in a multilingual group) to compare cultural practices, we will try to ensure that students from the same country do not work together (since that would defeat the object of the exercise). If the task is about people who are interested in particular leisure activities (sport, music, etc.), that might determine the make¬up of the pairs or groups.

- Changing groups: just because we put students in groups at the beginning of an activity does not mean that they have to stay in these groups until the end. The group may change while an activity continues. For example, students may start by listing vocabulary and then discuss it first in pairs, then in groups of four, then in groups of eight - or even 16. In an interview activity, students can start working in two main groups and then break into smaller groups for a role- play. If groups are planning something or discussing, members from other groups can come and visit them to share information and take different information back to their original group. A longer sequence may start with the teacher and the whole class before moving between pairwork, individual work and groupwork until it returns back to the whole-class grouping.

- Gender and status: we need to remember that in some contexts it may not be appropriate to have men and women working together. Similarly, when grouping students we may want to bear in mind the status of the individuals in their lives outside the classroom. This is especially true in business English groups where different tiers of management, for example, are represented in the group. We will need, in both these scenarios, to make ourselves aware of what is the norm so that we can then make informed decisions about how to proceed.

We make our pairing and grouping decisions based on a variety of factors. If we are concerned about the atmosphere of the whole class and some of the tensions in it, we may try to make friendship groups - always bearing in mind the need to foster an acceptance for working with all students in the group eventually. If our activity is based on fun, we may leave our grouping to chance. If, on the other hand, we are dealing with a non-homogeneous class (in terms of level) or if we have some students who are falling behind, we may stream groups so that we can help the weaker students while keeping the more advanced ones engaged in a different activity. We might, for example, stream pairs to do research tasks so that students with differing needs can work on different aspects of language.

One final point that needs stressing is that we should not always have students working with the same partners or group members. This creates what Sue Murray humorously refers to as ESP-PWOFP (English for the Sole Purpose of doing Pair Work with One Fixed Partner) (Murray 2000: 49). She argues persuasively that mixing and moving students around as a course progresses is good for classroom atmosphere and for individual engagement.

Procedures for pairwork and groupwork

Our role in pairwork and groupwork does not end when we have decided which students should work together, of course. We have other matters to address, too, not only before the activity starts, but also during and after it.

- Before: when we want students to work together in pairs or groups, we will want to follow an 'engage-instruct-initiate' sequence. This is because students need to feel enthusiastic about what they are going to do, they need to know what they are going to do, and they need to be given an idea of when they will have finished the task. Sometimes our instructions will involve a demonstration - when, for example, students are going to use a new information-gap activity or when we want them to use cards. On other occasions, where an activity is familiar, we may simply give them an instruction to practise language they are studying in pairs, or to use their dictionaries to find specific bits of information. The success of a pairwork or groupwork task is often helped by giving students a time when the activity should finish - and then sticking to it. This helps to give them a clear framework to work within. Alternatively in lighter- hearted activities such as a poem dictation, we can encourage groups to see who finishes first. Though language learning is not a contest (except, perhaps, a personal one), in game-like activities ' ... a slight sense of competition between groups does no harm' (Nuttall 1996: 164). The important thing about instructions is that the students should understand and agree on what the task is. To check that they do, we may ask them to repeat the instructions, or, in monolingual classes, to translate them into their first language.

- During: while students are working in pairs or groups we have a number of options. We could, for instance, stand at the front or the side of the class (or at the back or anywhere else) and keep an eye on what is happening, noting who appears to be stuck, disengaged or about to finish. In this position we can tune in to a particular pair or group from some distance away. We can then decide whether to go over and help them. An alternative procedure is often referred to as monitoring. This is where we go round the class, watching and listening to specific pairs and groups either to help them with the task or to collect examples of what they are doing for later comment and work. For example, we can stay with a group for a period of time and then intervene if and when we think it is appropriate or necessary, always bearing in mind what we have said about the difference between accuracy and fluency work. If students are involved in a discussion, for example, we might correct gently; if we are helping students with suggestions about something they are planning, or trying to move a discussion forwards, we can act as prompter, resource or tutor. In such situations we will often be responding to what they are doing rather than giving correction feedback. We will be helping them forwards with the task they are involved in. Where students fall back on their first language, we will do our best to encourage or persuade them back into English. When students are working in pairs or groups we have an ideal opportunity to work with individual students whom we feel would benefit from our attention. We also have a great chance to act as observer, picking up information about student progress, and seeing if we will have to 'troubleshoot'. But however we monitor, intervene or take part in the work of a pair or group, it is vital that we do so in a way that is appropriate to the students involved and to the tasks they are involved in.

- After: when pairs and groups stop working together, we need to organise feedback. We want to let them discuss what occurred during the groupwork session and, where necessary, add our own assessments and make corrections. Where pairwork or groupwork has formed part of a practice session, our feedback may take the form of having a few pairs or groups quickly demonstrate the language they have been using. We can then correct it, if and when necessary and this procedure will give both those students and the rest of the class good information for future learning and action. Where pairs or groups have been working on a task with definite right or wrong answers, we need to ensure that they have completed it successfully. Where they have been discussing an issue or predicting the content of a reading text, we will encourage them to talk about their conclusions with us and the rest of the class. By comparing different solutions, ideas and problems, everyone gets a greater understanding of the topic. Where students have produced a piece of work, we can give them a chance to demonstrate this to other students in the class. They can stick written material on noticeboards; they can read out dialogues they have written or play audio or video tapes they have made. Finally, it is vital to remember that constructive feedback on the content of student work can greatly enhance students' future motivation. The feedback we give on language mistakes is only one part of that process.

Troubleshooting

When we monitor pairs and groups during a groupwork activity, we are seeing how well they are doing and deciding whether or not to go over and intervene. But we are also keeping our eyes open for problems which we can resolve either on the spot or in future.

- Finishing first: a problem that frequently occurs when students are working in pairs or groups is that some of them finish earlier than others and/or show clearly that they have had enough of the activity and want to do something else. We need to be ready for this and have some way of dealing with the situation. Saying to them OK, you can relax for a bit while the others finish may be appropriate for tired students, but can make other students feel that they are being ignored. When we see the first pairs or groups finish the task, we might stop the activity for the whole class. That removes the problem of boredom, but it may be very demotivating for the students who haven't yet finished, especially when they are nearly there and have invested some considerable effort in the procedure. One way of avoiding the problems we have mentioned here is to have a series of challenging task-related extensions for early finishers so that when a group has finished early, we can give them an activity to complete while they are waiting. This will show the students that they are not just being left to do nothing. When planning groupwork it is a good idea for teachers to make a list of task-related extensions and other spare activities that first - finishing groups and pairs can be involved in. Even where we have set a time limit on pair- and groupwork, we need to keep an eye open to see how the students are progressing. We can then make the decision about when to stop the activity based on the observable (dis) engagement of the students and how near they all are to completing the task.

- Awkward groups: when students are working in pairs or groups we need to observe how well they interact together. Even where we have made our best judgements - based on friendship or streaming, for example - it is possible that apparently satisfactory combinations of students are not ideal. Some pairs may find it impossible to concentrate on the task in hand and instead encourage each other to talk about something else, usually in their first language. In some groups (in some educational cultures) members may defer to the oldest person there, or to the man in an otherwise female group. People with loud voices can dominate proceedings; less extrovert people may not participate fully enough. Some weak students may be lost when paired or grouped with stronger classmates. In such situations we may need to change the pairs or groups. We can separate best friends for pairwork; we can put all the high-status figures in one group so that students in other groups do not have to defer to them. We can stream groups or reorganise them in other ways so that all group members gain the most from the activity. One way of finding out about groups, in particular, is simply to observe, noting down how often each student speaks. If two or three observations of this kind reveal a continuing pattern, we can take the kind of action suggested above.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.