| Сколько по времени занимает проверка заданий? |

Error

Feedback during oral work

Though feedback - both assessment and correction - can be very helpful during oral work, teachers should not necessarily deal with all oral production in the same way. Decisions about how to react to performance will depend upon the stage of the lesson, the activity, the type of mistake made and the particular student who is making that mistake.

Accuracy and fluency

A distinction is often made between accuracy and fluency. We need to decide whether a particular activity in the classroom is designed to expect the students' complete accuracy - as in the study of a piece of grammar, a pronunciation exercise or some vocabulary work, for example - or whether we are asking the students to use the language as fluently as possible. We need to make a clear difference between 'non-communicative' and 'communicative' activities; whereas the former are generally intended to ensure correctness, the latter are designed to improve language fluency.

Most students want and expect us to give them feedback on their performance. For example, in one celebrated correspondence many years ago, a non-native-speaker teacher was upset when, on a teacher training course in the UK, her English trainers refused to correct any of her English because they thought it was inappropriate in a training situation. 'We find that there is practically no correcting at all,' the teacher wrote, 'and this comes to us as a big disappointment' (Lavezzo and Dunford 1993: 62). Her trainers were not guilty of neglect, however. There was a principle at stake: 'The immediate and constant correction of all errors is not necessarily an effective way of helping course participants improve their English’: the trainer replied on the same page of the journal.

This exchange of views exemplifies current attitudes to correction and some of the uncertainties around it. The received view has been that when students are involved in accuracy work, it is part of the teacher's function to point out and correct the mistakes the students are making. We might call this 'teacher intervention' - a stage where the teacher stops the activity to make the correction.

During communicative activities, however, it is generally felt that teachers should not interrupt students in mid-flow to point out a grammatical, lexical or pronunciation error, since to do so interrupts the communication and drags an activity back to the study of language form or precise meaning. Traditionally, according to one view of teaching and learning, speaking activities in the classroom, especially activities at the extreme communicative end of our continuum, were thought to act as a 'switch' to help learners transfer 'learnt' language to the 'acquired' store (Ellis 1982) or a 'trigger', forcing students to think carefully about how best to express the meanings they wish to convey (Swain 1985: 249). This view remains at the heart of the 'focus on forms' view of language learning. Part of the value of such activities lies in the various attempts that students have to make to get their meanings across; processing language for communication is, in this view, the best way of processing language for acquisition. Teacher intervention in such circumstances can raise stress levels and stop the acquisition process in its tracks.

If that is the case, the methodologist Tony Lynch argues, then students have a lot to gain from coming up against communication problems. Provided that they have some of the words and phrases necessary to help them negotiate a way out of their communicative impasses, they will learn a lot from so doing. When teachers intervene, not only to correct but also to supply alternative modes of expression to help students, they remove that need to negotiate meaning, and thus they may deny students a learning opportunity. In such situations teacher intervention may sometimes be necessary, but it is nevertheless unfortunate - even when we are using 'gentle correction'. In Tony Lynch's words, 'the best answer to the question of when to intervene in learner talk is: as late as possible' (Lynch 1997: 34).

Nothing in language teaching is quite that simple, of course. There are times during communicative activities when teachers may want to offer correction or suggest alternatives because the students' communication is at risk, or because this might be just the right moment to draw the students' attention to a problem. Furthermore, when students are asked for their opinions on this matter, they often have conflicting views. In a survey of all the students at a language school in south London, Philip Harmer found that whereas 38 per cent of the students liked the teacher to do correction work at the front of the class after the task had finished, 62 per cent liked being corrected at the moment of speaking (2005:74). It is worth pointing out, too, that intensive correction can be just as inappropriately handled during accuracy work as during fluency work. It often depends on how it is done, and, just as importantly, who it is done to. Correction is a highly personal business and draws, more than many other classroom interactions, on the rapport between teacher and students. And as Philip Harmer's study suggests, different students have different preferences.

For all these reasons, we need to be extremely sensitive about the way we give feedback and the way we correct. This means, for example, not reacting to absolutely every mistake that a student makes if this will demotivate that particular student. It means judging just the right moment to correct, taking into account the preferences of the group and of individual students. In communicative or fluency activities, it means deciding if and when to intervene at all, and if we do, what is the best way to do it. Perhaps, too, if we have time, we should talk to our students about feedback and correction and explain to them what we intend to do, and when and why, and then invite their own comments so that we can make a bargain with them about this aspect of classroom experience.

Feedback during accuracy work

As suggested above, correction is usually made up of two distinct stages. In the first, teachers show students that a mistake has been made, and in the second, if necessary, they help the students to do something about it. The first set of techniques we need to be aware of, then, is devoted to showing incorrectness. These techniques are only really beneficial for what we are assuming to be language 'slips' rather than embedded or systematic errors (due to the interlanguage stage the students have reached). When we show incorrectness, we are hoping that the students will be able to correct themselves once the problem has been pointed out. If they can't do this, however, we will need to move on to alternative techniques.

-

Showing incorrectness: this can be done in a number of different ways:

- Repeating: here we can ask the student to repeat what they have said, perhaps by saying Again? which, coupled with intonation and expression, will indicate that something isn't clear.

- Echoing: this can be a precise way of pin-pointing an error. We repeat what the student has said, emphasising the part of the utterance that was wrong, e.g. Flight 309 GO to Paris? (said with a questioning intonation) or She SAID me? It is an extremely efficient way of showing incorrectness during accuracy work.

- Statement and question: we can, of course, simply say Good try, but that's not quite right or Do people think that's correct? to indicate that something hasn't quite worked.

- Expression: when we know our classes well, a simple facial expression or a gesture (for example, a wobbling hand) may be enough to indicate that something doesn't quite work. This needs to be done with care as the wrong expression or gesture can, in certain circumstances, appear to be mocking or cruel.

- Hinting: a quick way of helping students to activate rules they already know (but which they have temporarily 'mislaid') is to give a quiet hint. We might just say the word tense to make them think that perhaps they should have used the past simple rather than the present perfect. We could say countable to make them think about a concord mistake they have made, or tell to indicate they have chosen the wrong word. This kind of hinting depends upon the students and the teacher sharing metalanguage (linguistic terms) which, when whispered to students, will help them to correct themselves.

-

Reformulation: a correction technique which is widely used both for accuracy and fluency work is for the teacher to repeat back a corrected version of what the student has said, reformulating the sentence, but without making a big issue of it. For example:

STUDENT: She said me I was late.

TEACHER: Oh, so she told you you were late, did she?

STUDENT: Oh yes, I mean she told me. So I was very unhappy and ...

Such reformulation is just a quick reminder of how the language should sound. It does not put the student under pressure, but clearly points the way to future correctness. Its chief attribute - in contrast to the other techniques mentioned above - is its unobtrusiveness.

In all the procedures above, teachers hope that students are able to correct themselves once it has been indicated that something is wrong. However, where students do not know or understand what the problem is (and so cannot be expected to resolve it), the teacher will want to help the students to get it right.

- Getting it right: if students are unable to correct themselves or respond to reformulation, we need to focus on the correct version in more detail. We can say the correct version, emphasising the part where there is a problem (e.g. Flight 309 GOES to Paris) before saying the sentence normally (e.g. Flight 309 goes to Paris), or we can say the incorrect part correctly (e.g. Not ‘go’, listen, ‘goes’). If necessary, we can explain the grammar (e.g. We say I go, you go, we go, but for he, she or it, we say goes. For example, 'He goes to Paris' or 'Flight 309 goes to Paris'), or the lexical issue, (e.g. We use 'juvenile crime' when we talk about crime committed by children; a 'childish crime' is an act that is silly because it's like the sort of thing a child would do). We will then ask the student to repeat the utterance correctly.

We can also ask students to help or correct each other. This works well where there is a genuinely cooperative atmosphere; the idea of the group helping all of its members is a powerful concept. Nevertheless, it can go horribly wrong where the error-making individual feels belittled by the process, thinking that they are the only one who doesn't know the grammar or vocabulary. We need to be exceptionally sensitive here, only encouraging the technique where it does not undermine such students. As we have said above, it is worth asking students for their opinions about which techniques they personally feel comfortable with.

Feedback during fluency work

The way in which we respond to students when they speak in a fluency activity will have a significant bearing not only on how well they perform at the time but also on how they behave in fluency activities in the future. We need to respond to the content, and not just to the language form; we need to be able to untangle problems which our students have encountered or are encountering, but we may well decide to do this after the event, not during it. Our tolerance of error in fluency sessions will be much greater than it is during more controlled sessions. Nevertheless, there are times when we may wish to intervene during fluency activities (especially in the light of students' preferences - see above), just as there are ways we can respond to our students once such activities are over.

-

Gentle correction: if communication breaks down completely during a fluency activity, we may well have to intervene. If our students can't think of what to say, we may want to prompt them forwards. If this is just the right moment to point out a language feature, we may offer a form of correction. Provided we offer this help with tact and discretion, there is no reason why such interventions should not be helpful. But however we do it, our correction will be more gentle: in other words, we will not stop the whole activity and insist on everyone saying the item correctly before being allowed to continue with their discussion. Gentle correction can be offered in a number of ways. We might simply reformulate what the student has said in the expectation that they will pick up our reformulation, even though it hardly interrupts their speech, e.g.

STUDENT 1: And when I go on holiday, I enjoy to ski in the winter and I like to surf in the summer.

TEACHER: Yes, I enjoy skiing, too.

STUDENT 1: Ah, yes, I enjoy skiing.

STUDENT 2: I don't enjoy skiing. It's too cold. What I like is ...

It is even possible that when students are making an attempt to say something they are not sure of, such reformulation or suggestion may help them to learn something new.

We can use a number of other techniques for showing incorrectness, too, such as echoing and expression, or even saying I shouldn't say X, say Y, etc. But because we do it gently, and because we do not move on to a ‘getting it right’ stage, our intervention is less disruptive than a more accuracy-based procedure would be.

However, we need to be careful of over-correction during a fluency stage. By constantly interrupting the flow of the activity, we may bring it to a standstill. What we have to judge, therefore, is whether a quick reformulation or a quick prompt may help the conversation move along without intruding too much or whether, on the contrary, it is not especially necessary and has the potential to get in the way of the conversation.

-

Recording mistakes: we frequently act as observers, watching and listening to students so that we can give feedback afterwards. Such observation allows us to give good feedback to our students on how well they have performed, always remembering that we want to give positive as well as negative feedback.

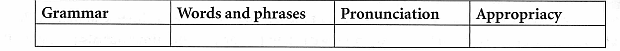

One of the problems of giving feedback after the event is that it is easy to forget what students have said. Most teachers, therefore, write down points they want to refer to later, and some like to use charts or other forms of categorisation to help them do this, as in Figure 9.3.

In each column we can note down things we heard, whether they were particularly good or incorrect or inappropriate. We might write down errors such as according to my opinion in the words and phrases column, or haven't been yesterday in the grammar column; we might record phoneme problems or stress issues in the pronunciation column and make a note of places where students disagreed too tentatively or bluntly in the appropriacy column.

We can also record students' language performance with audio or video recorders. In this situation the students might be asked to design their own charts like the one above so that when they listen or watch, they, too, will be writing down more and less successful language performance in categories which make remembering what they heard easier. Another alternative is to divide students into groups and have each group listen or watch for something different. For example, one group might focus on pronunciation, one group could listen for the use of appropriate or inappropriate phrases, while a third looks at the effect of the physical paralinguistic features that are used. If teachers want to involve students more - especially if they have been listening to an audiotape or watching a video - they can ask them to write up any mistakes they think they heard on the board. This can lead to a discussion in which the class votes on whether they think the mistakes really are mistakes.

Another possibility is for the teacher to transcribe parts of the recording for future study. However, this takes a lot of time!

- After the event: when we have recorded student performance, we will want to give feedback to the class. We can do this in a number of ways. We might want to give an assessment of an activity, saying how well we thought the students did in it, and getting the students to tell us what they found easiest or most difficult. We can put some of the mistakes we have recorded up on the board and ask students first if they can recognise the problem, and then whether they can put it right. Alternatively, we can write both correct and incorrect words, phrases or sentences on the board and have the students decide which is which. When we write examples of what we heard on the board, it is not generally a good idea to say who made the mistakes since this may expose students in front of their classmates. Indeed, we will probably want to concentrate most on those mistakes which were made by more than one person. These can then lead on to quick teaching and re-teaching sequences. Another possibility is for teachers to write individual notes to students, recording mistakes they heard from those particular students with suggestions about where they might look for information about the language - in dictionaries, grammar books or on the Internet.

Feedback on written work

The way we give feedback on writing will depend on the kind of writing task the students have undertaken, and the effect we wish to create. When students do workbook exercises based on controlled testing activities, we will mark their efforts right or wrong, possibly pencilling in the correct answer for them to study. However, when we give feedback on more creative or communicative writing (whether letters, reports, stories or poems), we will approach the task with circumspection and clearly demonstrate our interest in the content of the students' work. A lot will depend on whether we are intervening in the writing process (where students are composing various written drafts before producing a final version ), or whether we are marking a finished product. During the writing process we will be responding rather than correcting.

Responding

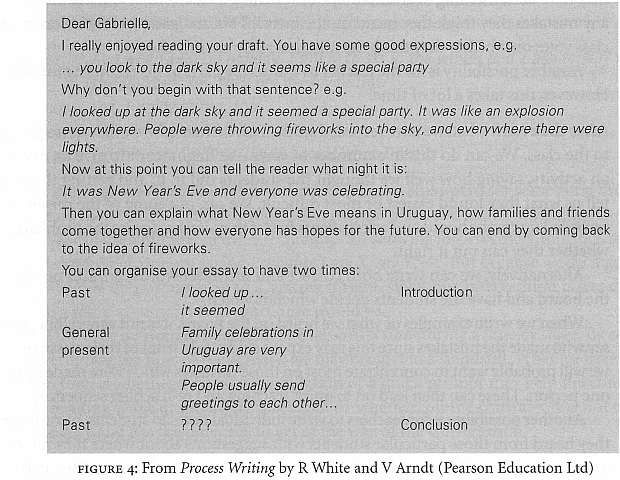

When we respond, we say how the text appears to us and how successful we think it has been (we give a medal, in other words) before suggesting how it could be improved (the mission). Such responses are vital at various stages of the writing process cycle. The comments we offer students need to appear helpful and not censorious. Sometimes they will be in the margin of the students' work or, on a computer, they can be written as viewable comments either by using an editing program or by writing in comments in a different colour. If we want to offer more extensive comments, we may need a separate piece of paper - or separate computer document. Consider this example in which the teacher is responding in the form of a letter to a student's first draft of a composition about New Year's Eve:

This type of feedback takes time, of course, but it can be more useful to the student than a draft covered in correction marks. It is designed specifically for situations in which the student will go back and review the draft before producing a new version.

When we respond to a final written product (an essay or a finished project), we can say what we liked, how we felt about the text and what we think the students might do next time if they are going to write something similar.

Another constructive way of responding to students' written work is to show alternative ways of writing through reformulation. Instead of providing the kind of comments in the example above, we might say, I would express this paragraph slightly differently from you, and then re-write it, keeping the original intention as far as possible, but avoiding any of the language or construction problems which the student's original contained. Such reformulation is extremely useful for students since by comparing their version with yours they discover a lot about the language. However, it has to be done sympathetically, since we might end up 'steamrollering' our own view of things, forcing the student to adopt a different voice from the one they wanted to use.

Correcting

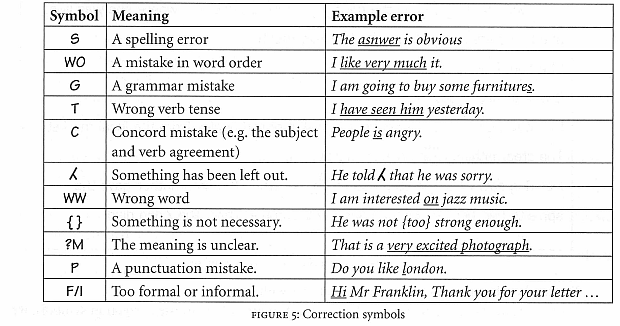

Many teachers use correction codes to indicate that students have made mistakes in their written work. These codes can be written into the body of the text itself or in the margin. This makes correction much neater and less threatening than random marks and comments. Different teachers use different symbols, but Figure 9.5 shows some of the more common ones.

In order for students to benefit from the use of symbols such as these, they need to be trained in their use. We can also correct by putting ticks against good points (or another appropriate symbol, such as, for example, a circle if the lessons are taking place in Japan) and underlining problems. We can write summarising comments at the end of a student's work saying what was appropriate and what needs correcting.

Involving students

So far we have discussed the teacher)s feedback to students. But we can also encourage students to give feedback to each other. Such peer review has an extremely positive effect on group cohesion. It encourages students to monitor each other and, as a result, helps them to become better at self monitoring. James Muncie suggests a further advantage, namely that whereas students see teacher comment as coming from an expert, as a result of which they feel obliged to do what is suggested, even when we are only making suggestions, they are much more likely to be provoked into thinking about what they are writing if the feedback comes from one of their peers (Muncie 2000). Thus when responding to work during the drafting stage peer feedback is potentially extremely beneficial. However, in order to make sure that the comment is focused we might want to design a form such as the one suggested by Victoria Chan (2001) where students are given sentences to complete such as My immediate reactions to your piece of writing are ... , I like the part ... , I'm not sure about ... , The specific language errors I have noticed are ... ) etc.

In her book on writing, Tricia Hedge suggests letting the students decide (with teacher guidance) what they think the most important things to look out for in a piece of writing are (Hedge 1988:54). They can give their opinions about whether spelling is more important than handwriting or whether originality of ideas should interest the feedback giver more than, say, grammatical correctness. They can be asked for their opinions on the best grading system, too. In consultation with the teacher, therefore, they can come up with their own feedback kit.

We can also encourage students to self-monitor by getting them to write a checklist of things to look out for when they evaluate their own work during the drafting process (Harmer 2004: 121). The more we encourage them to be involved in giving feedback to each other, or to evaluate their own work successfully, the better they will be able to develop as successful writers.

Finishing the feedback process

Except where students are taking achievement tests, written feedback is designed not just to give an assessment of the students' work, but also to help and teach. We give feedback because we want to affect our students' language use in the future as well as comment upon its use in the past. When we respond to first and second written drafts of a written assignment, therefore, we expect a new version to be produced which will show how the students have responded to our comments. In this way feedback is part of a learning process, and we will not have wasted our time. Our reason for using codes and symbols is the same: if students can identify the mistakes they have made, they are then in a position to correct them. The feedback process is only really finished once they have made these changes. And if students consult grammar books or dictionaries as a way of resolving some of the mistakes we have signalled for them, the feedback we have given has had a positive outcome. If, on the contrary, when we return corrected work, the students put it straight into a file or lose it, then the time we spent responding or correcting has been completely wasted.

Burning the midnight oil

'Why burn the midnight oil?' asks Icy Lee (2005b) in an article which discusses the stress of written feedback for students and teachers. For students, the sight of their work covered in corrections can cause great anxiety. For teachers, marking and correcting take up an enormous amount of time (Lee found that the 200 Hong Kong teachers she interviewed spent an average of 20-30 hours a week marking). Both teachers and students deserve a break from this drudgery.

Along with other commentators, Lee has a number of ways of varying the amount of marking and the way teachers do it. These include:

- Selective marking: we do not need to mark everything all the time. If we do, it takes a great deal of time and can be extremely demotivating. It is often far more effective to tell students that for their next piece of work we will be focusing specifically on spelling, or specifically on paragraph organisation, or on verb tenses, for example. We will have less to correct, the students will have fewer red marks to contend with, and while they preparing their work, students will give extra special attention to the area we have identified.

- Different error codes: there is no reason why students and teachers should always use the same error codes (see above). At different levels and for different tasks we may want to make shorter lists of possible errors, or tailor what we are looking at for the class in question.

- Don't mark all the papers: teachers may decide only to mark some of the scripts they are given - as a sample of what the class has done as a whole. They can then use what they find there for post-task teaching with the whole class.

- Involve the students: teachers can correct some of the scripts and students can look at some of the others. As we saw above, peer correction has extremely beneficial results.

We are not, of course, suggesting abandoning teacher feedback. But we need to be able to think creatively about how it can best be done in the interests of both students and teachers.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.

WRITING REMEDIAL EXERCISES.

As you can see, dealing with errors is a complex business as students may make multiple errors in a single statement. The aim of a remedial exercise is to focus the students’ attention on a single point of error in order to help them with understanding how it works. Remedial means fixing or making better and remedial exercises come after the students have made the error with the aim of fixing it. (Look back at Unit 2 Module 1 to remind yourself of what good language exercises look like.)

SELF-CHECK 3:5 6

Which of these two exercises will be of more help to a student to fix an error?

Exercise 1

Teacher’s Note: The students need remedial study in all verb tenses (particularly present perfect - I had been in London).

Verb tense. Write in the correct form of the verb shown in parentheses to complete the sentence.

- Jason (work) _________________ at the office on the corner.

- Last year he (work) ________________ in New York City.

- When he finishes college in 2016, he (work) ___________________ in his father’s business.

- If Jason had not gone to college, he (work) ____________________ at the deli.

- Since January, he (work) _____________________ twenty hours each week.

Exercise 2

On five o'clock I want to eat my tea. - At

The student has made an error with a preposition of time. We use atwith a particular time such as a clock time or meal time, such as at half past five or at breakfast. We also use at with holiday periods of 2 or 3 days, such as at Christmas, or at the weekend. On is only used for specific days, for example on Tuesday. They should also note that in should be used for longer periods or with a part of the day. For example, in the morning and in 2006.

Select the correct answers from the words below the sentences;

A) "I was born ____ 11 o’clock at night ____ 1975.

a) in b) on c) at d) to

B) "Every morning I go to school ____ half past 7"

a) on b) at c) in

etc - 5 more example sentences.

You are right if you chose the second exercise. Remedial exercises need a clear and ‘tight’ focus on a specific point. There are too many tenses in the first exercise and too much information for the students to cope with. The second one focuses clearly on prepositions of time.

EXTRA HINTS FOR GOOD EXERCISES

Tense exercises and exercises about articles are better done in paragraphs than in separate sentences as they are less ambiguous and students can see how the relationships between words work in a context. (see Unit 2 Module 1)

Word order exercises are not just a matter of jumbling up words and reordering- you need to think about what part of grammar caused the word order mistake - was it a word order mistake with adverbs? Or question forms?

‘Grammar errors’ covers a wide area but ensure the remedial exercises focus on one error area only.