|

1 октября отправила на проверку первое задание, до сих пор не проверено, по этой причине не могу пройти последующие тесты. |

Listening and Reading

Film and video

So far we have talked about recorded material as audio material only. But of course, we can also have students listen while they watch film clips on video, DVD or online. There are many good reasons for encouraging students to watch while they listen. In the first place, they get to see 'language in use'. This allows them to see a whole lot of paralinguistic behaviour. For example, they can see how intonation matches facial expression and what gestures accompany certain phrases (e.g. shrugged shoulders when someone says I don't know), and they can pick up a range of cross-cultural clues. Film allows students entry into a whole range of other communication worlds: they see how different people stand when they talk to each other (how close they are, for example) or what sort of food people eat. Unspoken rules of behaviour in social and business situations are easier to see on film than to describe in a book or hear on an audio track. Just like audio material, filmed extracts can be used as a main focus of a lesson sequence or as parts of other longer sequences. Sometimes we might get students to watch a whole programme, but at other times they will only watch a short two- or three-minute sequence. Because students are used to watching film at home - and may therefore associate it with relaxation - we need to be sure that we provide them with good viewing and listening tasks so that they give their full attention to what they are hearing and seeing.

Finally, it is worth remembering that students can watch a huge range of film clips on the Internet at sites such as You Tube (www.youtube.com) where people of all ages and interests can post film clips in which they talk or show something. Everything students might want is out there in cyberspace, so they can do extensive or intensive watching and then come and tell the class about what they have seen. Just as with extensive listening, the more they do this, the better.

Viewing techniques

All of the following viewing techniques are designed to awaken the students' curiosity through prediction so that when they finally watch the film sequence in its entirety, they will have some expectations about it.

- Fast forward: the teacher presses the play button and then fast forwards the DVD or video so that the sequence shoots past silently and at great speed, taking only a few seconds. When it is over, the teacher can ask students what the extract was all about and whether they can guess what the characters were saying.

- Silent viewing (for language): the teacher plays the film extract at normal speed but without the sound. Students have to guess what the characters are saying. When they have done this, the teacher plays it with sound so that they can check to see if they guessed correctly.

- Silent viewing (for music): the same technique can be used with music. Teachers show a sequence without sound and ask students to say what kind of music they would put behind it and why. When the sequence is then shown again, with sound, students can judge whether they chose music conveying the same mood as that chosen by the film director.

- Freeze frame: at any stage during a video sequence we can freeze the picture, stopping the participants dead in their tracks. This is extremely useful for asking the students what they think will happen next or what a character will say next.

- Partial viewing: one way of provoking the students' curiosity is to allow them only a partial view of the pictures on the screen. We can use pieces of card to cover most of the screen, only leaving the edges on view. Alternatively, we can put little squares of paper all over the screen and remove them one by one so that what is happening is only gradually revealed. A variation of partial viewing occurs when the teacher uses a large ‘divider’, placed at right angles to the screen so that half the class can only see one half of the screen, while the rest of the class can only see the other half. They then have to say what they think the people on the other side saw.

Listening (and mixed) techniques

Listening routines, based on the same principles as those for viewing, are similarly designed to provoke engagement and expectations.

- Pictureless listening (language): the teacher covers the screen, turns the monitor away from the students or turns the brightness control right down. The students then listen to a dialogue and have to guess such things as where it is taking place and who the speakers are. Can they guess their age, for example? What do they think the speakers actually look like?

- Pictureless listening (music): where an excerpt has a prominent music track students can listen to it and then say - based on the mood it appears to convey - what kind of scene they think it accompanies and where it is taking place.

- Pictureless listening (sound effects): in a scene without dialogue students can listen to the sound effects to guess what is happening. For example, they might hear the lighting of a gas stove, eggs being broken and fried, coffee being poured and the milk and sugar stirred in. They then tell the story they think they have just heard.

- Picture or speech: we can divide the class in two so that half of the class faces the screen and half faces away. The students who can see the screen have to describe what is happening to the students who cannot. This forces them into immediate fluency while the non-watching students struggle to understand what is going on, and is an effective way of mixing reception and production in spoken English. Halfway through an excerpt, the students can change round.

- Subtitles: there are many ways we can use subtitled films. John Field (2000a: 194) suggests that one way to enable students to listen to authentic material is to allow them to have subtitles to help them. Alternatively, students can watch a film extract with subtitles but with the sound turned down. Every time a subtitle appears, we can stop the film and the students have to say what they think the characters are saying in English. With DVDs which have the option to turn off the subtitles, we can ask students to say what they would write for subtitles and then they can compare theirs with what actually appears. Subtitles are only really useful, of course, when students all share the same L1. But if they do, the connections they make between English and their language can be extremely useful.

Listening lesson sequences

No skill exists in isolation (which is why skills are integrated in most learning sequences). Listening can thus occur at a number of points in a teaching sequence. Sometimes it forms the jumping-off point for the activities which follow. Sometimes it may be the first stage of a 'listening and acting out' sequence where students role-play the situation they have heard on the recording. Sometimes live listening may be a prelude to a piece of writing which is the main focus of a lesson. Other lessons, however, have listening training as their central focus. However much we have planned a lesson, we need to be flexible in what we do. Nowhere is this more acute than in the provision of live listening, where we may, on the spur of the moment, feel the need to tell a story or act out some role. Sometimes this will be for content reasons - because a topic comes up - and sometimes it may be a way of re-focusing our students' attention. Most listening sequences start with a Type 1 task before moving on to more specific Type 2 explorations of the text. In general, we should aim to use listening material for as many purposes as possible - both for practising a variety of skills and as source material for other activities - before students finally become tired of it.

Examples of listening sequences

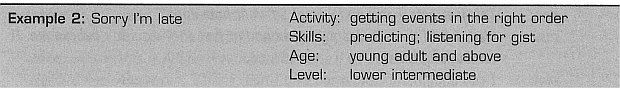

In the following examples, the listening activity is specified, the skills which are involved are detailed and the way that the listening text can be used within a lesson is explained.

Where possible, teachers can bring strangers into the class to talk to the students or be interviewed by them. Although students will be especially interested in them if they are native speakers of the language, there is no reason why they should not include any competent English speakers. The teacher briefs the visitor about the students' language level, pointing out that they should be sensitive about the level of language they use, but not speak to the students in a very unnatural way. They should probably not go off into lengthy explanations, and they may want to consider speaking especially clearly.

The teacher takes the visitor into the classroom without telling the students who or what the visitor is. In pairs or groups, they try to guess as much as they can about the visitor. Based on their guesses, they write questions that they wish to ask.

The visitor is now interviewed with the questions the students have written. As the interview proceeds, the teacher encourages them to seek clarification where things are said that they do not understand. The teacher will also prompt the students to ask follow-up questions; if a student asks Where are you from? and the visitor says that he comes from Scotland, he can then be asked Where in Scotland? or What's Scotland like?

During the interview the students make notes. When the interviewee has gone, these notes form the basis of a written follow-up. The students can write a short biographical piece about the person - for example, as a profile page from a magazine. They can discuss the interview with their teacher, asking for help with any points they are still unclear about. They can also role-play similar interviews among themselves.

We can make pre-recorded interviews in coursebooks more interactive by giving students the interviewer's questions first so that they can predict what the interviewee will say.

A popular technique for having students understand the gist of a story - but which also incorporates prediction and the creation of expectations - involves the students in listening in order to put pictures in the sequence in which they hear them. In this example, students look at the following four pictures:

They are given a chance, in pairs or groups, to say what they think is happening in each picture. The teacher will not confirm or deny their predictions. Students are then told that they are going to listen to a recording and that they should put the pictures in the correct chronological order (which is not the same as the order of what they hear). This is what is on the tape:

ANNA: Morning Stuart. What time do you call this?

STUART: Er, well, yes, I know, umm. Sorry. Sorry I'm Late.

ANNA: Me, too. Well?

STUART: I woke up Late.

ANNA: You woke up Late.

STUART: 'Fraid so. I didn't hear the alarm.

ANNA: Oh, so you were out last night?

STUART: Yes. Yes. 'Fraid so. No, I mean, yes, I went out last night, so what?

ANNA: So what happened?

STUART: Well, when I saw the time I jumped out of bed, had a quick shower, obviously, and ran out of the house. But when I got to the car ...

ANNA: Yes? When you got to the car?

STUART: Well, this is really stupid, but I realised I'd forgotten my keys.

ANNA: Yes, that is really stupid.

STUART: And the door to my house was shut.

ANNA: Of course it was! So what did you do? How did you get out of that one?

STUART: I ran round to the garden at the back and climbed in through the window.

ANNA: Quite a morning!

STUART: Yeah, and someone saw me and called the police.

ANNA: This just gets worse and worse! So what happened?

STUART: Well, I told them it was my house and at first they wouldn't believe me. It took a long time!

ANNA: I can imagine.

STUART: And you see, that's why I'm late!

The students check their answers with each other and then, if necessary, listen again to ensure that they have the sequence correct (C, A, D, B). The teacher can now get the students to listen again or look at the tapescript, noting phrases of interest, such as those that Stuart uses to express regret and apology (Sorry I'm late, I woke up late, 'Fraid so ), Anna's insistent questioning (What time do you call this? Well? So what happened? So what did you do? How did you get out of that one? ) and her use of repetition both to be judgmental and to get Stuart to keep going with an explanation she obviously finds ridiculous (You woke up late, Yes, that is really stupid, Quite a morning! I can imagine). The class can then go on to role-play similar scenes in which they have to come up with stories and excuses for being late for school or work.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.