| Сколько по времени занимает проверка заданий? |

Listening and Reading

Now consider the following extract:

Extensive and intensive reading

To get maximum benefit from their reading, students need to be involved in both extensive and intensive reading. Whereas with the former, a teacher encourages students to choose for themselves what they read and to do so for pleasure and general language improvement, the latter is often (but not exclusively) teacher-chosen and directed. It is designed to enable students to develop specific receptive skills such as reading for gist (or general understanding - often called skimming ), reading for specific information (often called scanning ), reading for detailed comprehension or reading for inference (what is 'behind' the words) and attitude .

Extensive reading

We have discussed the importance of extensive reading for the development of our students' word recognition - and for their improvement as readers overall. But it is not enough to tell students to 'read a lot'; we need to offer them a programme which includes appropriate materials, guidance, tasks and facilities, such as permanent or portable libraries of books.

Extensive reading materials: one of the fundamental conditions of a successful extensive reading programme is that students should be reading material which they can understand. If they are struggling to understand every word, they can hardly be reading for pleasure - the main goal of this activity. This means that we need to provide books which either by chance, or because they have been specially written, are readily accessible to our students.

Specially written materials for extensive are often referred to as graded readers or simplified readers. They can take the form of original fiction and non-fiction books as well as simplifications of established works of literature. Such books succeed because the writers or adaptors work within specific lists of allowed words and grammar. This means that students at the appropriate level can read them with ease and confidence. At their best, despite the limitations on language, such books can speak to the reader through the creation of atmosphere and/or compelling plot lines.

To encourage students to read this kind of learner literature - or any other texts which may be comprehensible in the same way - we need to act in the following ways:

Setting up a library: in order to set up an extensive reading programme, we need to build up a library of suitable books. Although this may appear costly, it will be money well spent. If necessary, we should persuade our schools and institutions to provide such funds or raise money through other sources. If possible, we should organise static libraries in the classroom or in some other part of the school. If this is not possible, we need to work out some way of carrying the books around with us - in boxes or on trolleys.

The role of the teacher in extensive reading programmes: most students will not do a lot of extensive reading by themselves unless they are encouraged to do so by their teachers. Clearly, then, our role is crucial. We need to promote reading and by our own espousal of reading as a valid occupation, persuade students of its benefits. Perhaps, for example, we can occasionally read aloud from books we like and show, by our manner of reading, how exciting books can be. Having persuaded our students of the benefits of extensive reading, we can organise reading programmes where we indicate to them how many books we expect them to read over a given period. We can explain how they can make their choice of what to read, making it clear that the choice is theirs, but that they can consult other students' reviews and comments to help them make that choice. We can suggest that they look for books in a genre (be it crime fiction, romantic novels, science fiction, etc.) that they enjoy, and that they make appropriate level choices. We will act throughout as part organiser, part tutor.

Extensive reading tasks: because students should be allowed to choose their own reading texts, following their own likes and interests, they will not all be reading the same texts at once. For this reason - and because we want to prompt students to keep reading - we should encourage them to report back on their reading in a number of ways.

One approach is to set aside a time at various points in a course - say every two weeks - at which students can ask questions and/or tell their classmates about books they have found particularly enjoyable or noticeably awful. However, if this is inappropriate because not all students read at the same speed (or because they often do not have much to say about the book in front of their colleagues), we can ask them each to keep a weekly reading diary, either on its own or as part of any learning journal they may be writing. Students can also write short book reviews for the class noticeboard. At the end of a month, a semester or a year, they can vote on the most popular book in the library. Other teachers have students fill in reading record charts (where they record title, publisher, level, start and end dates, comments about level and a good/fair/poor overall rating), they ask students to keep a reading notebook (where they record facts and opinions about the books they have gone through) or they engage students in oral interviews about what they are reading.

Intensive reading: the roles of the teacher

In order to get students to read enthusiastically in class, we need to work to create interest in the topic and tasks. However, there are further roles we need to adopt when asking students to read intensively:

- Organiser: we need to tell students exactly what their reading purpose is, give them clear instructions about how to achieve it and explain how long they have to do this. Once we have said You have four minutes for this, we should not change that time unless observation suggests that it is necessary.

- Observer: when we ask students to read on their own, we need to give them space to do so. This means restraining ourselves from interrupting that reading, even though the temptation may be to add more information or instructions. While students are reading we can observe their progress since this will give us valuable information about how well they are doing individually and collectively. It will also tell us whether to give them some extra time or, instead, move to organising feedback more quickly than we had anticipated.

- Feedback organiser: when our students have completed the task, we can lead a feedback session to check that they have completed it successfully. We may start by having them compare their answers in pairs and then ask for answers from the class in general or from pairs in particular. Students often appreciate giving paired answers like this since, by sharing their knowledge, they are also sharing their responsibility for the answers. When we ask students to give answers, we should always ask them to say where in the text they found the relevant information. This provokes a detailed study of the text which will help them the next time they come to a similar reading passage. It also tells us exactly what comprehension problems they have if and when they get answers wrong. It is important to be supportive when organising feedback after reading if we are to counter any negative feelings students might have about the process, and if we wish to sustain their motivation.

- Prompter: when students have read a text, we can prompt them to notice language features within it. We may also, as controllers, direct them to certain features of text construction, clarifying ambiguities and making them aware of issues of text structure which they had not come across previously.

Intensive reading: the vocabulary question

A common paradox in reading lessons is that while teachers are encouraging students to read for general understanding, without worrying about the meaning of every single word, the students, on the other hand, are desperate to know what each individual word means! Given half a chance, many of them would rather tackle a reading passage with a dictionary (electronic or otherwise) in one hand and a pen in the other to write translations all over the page! It is easy to be dismissive of such student preferences, yet as Carol Walker points out, 'It seems contradictory to insist that students "read for meaning" while simultaneously discouraging them from trying to understand the text at a deeper level than merely gist' (1998: 172). Clearly, we need to find some accommodation between our desire to have students develop particular reading skills (such as the ability to understand the general message without understanding every detail) and their natural urge to understand the meaning of every single word.

One way of reaching a compromise is to strike some kind of a bargain with a class whereby they will do more or less what we ask of them provided that we do more or less what they ask of us. Thus we may encourage students to read for general understanding without understanding every word on a first or second read-through. But then, depending on what else is going to be done, we can give them a chance to ask questions about individual words and/or give them a chance to look them up. That way both parties in the teaching-learning transaction have their needs met. A word of caution needs to be added here. If students ask for the meaning of all the words they do not know - and given some of the problems inherent in the explaining of different word meanings - the majority of a lesson may be taken up in this way. We need, therefore, to limit the amount of time spent on vocabulary checking in the following ways:

- Time limit: we can give a time limit of, say, five minutes for vocabulary enquiry, whether this involves dictionary use, language corpus searches or questions to the teacher.

- Word/phrase limit: we can say that we will only answer questions about five or eight words or phrases.

- Meaning consensus: we can get students to work together to search for and find word meanings. To start the procedure, individual students write down three to five words from the text they most want to know the meaning of. When they have each done this, they share their list with another student and come up with a new joint list of only five words. This means they will probably have to discuss which words to leave out. Two pairs join to make new groups of four and once again they have to pool their lists and end up with only five words. Finally (perhaps after new groups of eight have been formed - it depends on the atmosphere in the class), students can look for meanings of their words in dictionaries and/or we can answer questions about the words which the groups have decided on. This process works for two reasons. In the first place, students may well be able to tell each other about some of the words which individual students did not know. More importantly, perhaps, is the fact that by the time we are asked for meanings, the students really do want to know them because the intervening process has encouraged them to invest some time in the meaning search. 'Understanding every word' has been changed into a cooperative learning task in its own right.

In responding to a natural hunger for vocabulary meaning, both teachers and students will have to compromise. It's unrealistic to expect only one-sided change, but there are ways of dealing with the problem which make a virtue out of what seems - to many teachers - a frustrating necessity.

Intensive reading: letting the students in

It is often the case that the comprehension tasks we ask students to do are based on tasks in a coursebook. In other words, the students are responding to what someone else has asked them to find out. But students are far more likely to be engaged in a text if they bring their own feelings and knowledge to the task, rather than only responding to someone else's ideas of what they should find out. One of the most important questions we can ever get students to answer is Do you like the text? (Kennedy 2000a and b). The question is important because if we only ever ask students technical questions about language, we are denying them any affective response to the content of the text. By letting them give voice (if they wish) to their feelings about what they have read, we are far more likely to provoke the 'cuddle factor' than if we just work through a series of exercises.

Another way of letting the students in is to allow them to create their own comprehension task. A popular way of doing this - when the text is about people, events or topics which everyone knows something about - is to discuss the subject of the text with the class before they read. We can encourage them to complete a chart (on the board) with things they know or don't know (or would like to know) about the text, e.g.

This activity provides a perfect lead-in since students will be engaged, will activate their schemata, and will, finally, end up with a good reason to read which they themselves have brought into being. Now they read the text to check off all the items they have put into the three columns. The text may not give them all the answers, of course, nor may it confirm (or even refute) what they have put in the left-hand column. Nevertheless, the chances are that they will read with considerably more interest than for some more routine task.

Another involving way of reading is to have students read different texts and then share the information they have gathered in order to piece together the whole story. This is called jigsaw reading.

Reading lesson sequences

We use intensive reading sequences in class for a number of reasons. We may want to have students practise specific skills such as skimming/reading for general understanding or 'gist' or scanning/reading to extract specific information. We may, on the other hand, get students to read texts for communicative purposes, as part of other activities, as sources of information, or in order to identify specific uses of language.

Most reading sequences involve more than one reading skill. We may start by having students read for gist and then get them to read the text again for detailed comprehension; they may start by identifying the topic of a text before scanning the text quickly to recover specific information; they may read for specific information before going back to the text to identify features of text construction.

Examples of reading sequences

In the following example, the reading activity is specified, the skills which are involved detailed, and the way that the text can be used within a lesson is explained.

In this example, students predict the content of a text not from a picture, but from a few tantalising clues they are given (in the form of phrases from the passage they will read).

The teacher gives each student in the class a letter from A to E. She tells all the students to close their eyes. She then asks all the students with the letter A to open their eyes and shows them the word lion, written large so that they can see it. Then she makes them close their eyes again and this time shows the B students the phrase racial groups. She shows the C students the phrase paper aeroplanes, the D students the word tattoos and the E students the word guard. She now puts the students in groups of five, each composed of students A-E. By discussing their words and phrases, each group has to try to predict what the text is all about. The teacher can go round the groups encouraging them and, perhaps, feeding them with new words like cage, the tensest man or moral authority, etc. Finally, when the groups have made some predictions, the teacher asks them whether they would like to hear the text that all the words came from, as a prelude to reading the following text aloud, investing it with humour and drama, making the reading dramatic and enjoyable.

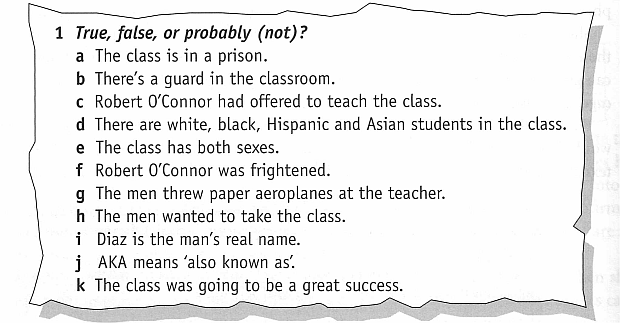

The students now read the text for themselves to answer the following detailed comprehension questions:

Before moving on to work with the content of the text, the teacher may well take advantage of the language in it to study some aspects that are of interest. For example, how is the meaning of would different in the sentences I ... wondered what I would do if he refused and a teacher ... who ... would turn towards the board ... ? Can students make sentences using the same construction as He was easily the tensest man I had ever seen (e.g. He/She was easily the(superlative adjective + noun) I had ever (past participle) or I could tell you my real name, but then I'd have to kill you (e.g. I could .., but then I'd have to .. ). The discussion possibilities for this text are endless. How many differences are there between Robert O'Connor's class and the students' own class? How many similarities are there? How would they (the students) handle working in a prison? Should prisoners be given classes anyway, and if so, of what kind? What would the students themselves do if they were giving their first English class in a prison or in a more ordinary school environment? Part of this sequence has involved the teacher reading aloud. This can be very powerful if it is not overdone. By mixing the skills of speaking, listening and reading, the students have had a rich language experience, and because they have had a chance to predict content, listen, read and then discuss the text, they are likely to be very involved with the procedure.

Adapted from The Practice of English Language Teaching, Jeremy Harmer 2007, Longman.

Reference

We recommend the following Teaching Reading skills in a foreign Language

Teaching Reading skills in a foreign Language ISBN 9781405080057

A revised edition of Christine Nuttall's established text on the teaching of reading skills in a foreign language. It examines the skills required to read effectively and suggests classroom strategies for developing them. A new chapter on testing reading is provided by Charles Alderson.

A revised edition of Christine Nuttall's established text on the teaching of reading skills in a foreign language. It examines the skills required to read effectively and suggests classroom strategies for developing them. A new chapter on testing reading is provided by Charles Alderson.

You can buy your books through our website at http://www.eslbooks.ru by clicking on the Bookshop section (Teacher theory and practice). You will find references to other titles as well as several websites which offer EFL material on the internet in the further research boxes at the end of each section of the course.